Who Has Questions About Interest Rates?

[ad_1]

I was staring out the window last Wednesday, feeling sick, envious, sad, guilty, and confused.

What a cornucopia of emotions, right?

I felt sick because I was sick. It wasn’t COVID, much to the dismay of some of the readers, it was most definitely something fierce.

I felt envious because I was watching a jogger pass by, and having sprained my ankle on April 11th, I, unfortunately, haven’t run since that magical 10K in Hampstead Heath in London, two days prior.

I felt sad because, well, it’s human nature to feel bad when things aren’t going your way – like being sick, like missing work, like not being able to run.

Then, I felt guilty for feeling sad, because this could not possibly be a better example of “first world problems.”

Lastly, I felt confused, because my phone kept beeping out of control, and what was an otherwise normal day had now picked up substantially, just in the last thirty seconds.

I was actually on a call at the time, and I often take calls from my home office while looking out the window. If you’re ever walking by and you see me staring at you, it’s totally cool, I’m not lurking, I’m just on the phone.

When I finished my call, I looked at my phone. I had about ten text messages, and anybody who knows me is aware that I’m not a big texter, so that’s a lot for me. There were fourteen emails as well, and this was all during the course of a fifteen or twenty minute phone call.

What was going on?

Well, it appeared that within this 15-20 minute window, the Bank of Canada announced that they would raise the benchmark lending rate by 100 basis points, or a full 1.00%. Not fifty basis points like they did previously, not seventy-five basis points like they teased that they ‘might’ last month, but rather a full one-hundred basis points, the likes of which many of us have never seen.

Full point!!!

That was the first text message I saw, and the meaning wasn’t quite received until I read the next one.

Holy fucking shit balls! A hundred points!

Ah, now the first message was in context.

But there was more.

Now what? The market going to shit, bud?

One from a client:

David, we just heard about the interest rate hike! Is our house going to go down in value?

One from a friend:

Saw the BOC hike. Have a fun 24 hours!

Another from a client:

“Take variable,” you told me last summer. Thanks David!!! 😜

She and I aren’t exactly married, so not really my fault on this one, but great to hear from her, nonetheless.

I think you get the picture; I don’t need to go through them all, but literally within a twenty-minute period, my phone lit up like a Jackolantern on the thirty-first of October…

I was surprised, and not in any cliche sense of the word. To describe my surprise as an “understatement” would be, in itself, an understatement.

Never did the idea of a 100-point rate hike enter my mind, and I’m somebody who tries to think of everything.

Last month, I wrote that we’re going to see a 50-basis point hike and that Tiff Macklem and the boys “teasing” a seventy-five point hike was just their egos at play, and perhaps attempts to scare people into taking immediate action to plan for an interest rate environment that wouldn’t actually come.

A 100-basis point hike, for those who didn’t read a single article, let alone headline, last week, hasn’t taken place in this country in almost a quarter-century.

Here’s the Bank of Canada’s official statement:

The Bank of Canada today increased its target for the overnight rate to 2½%, with the Bank Rate at 2¾% and the deposit rate at 2½%. The Bank is also continuing its policy of quantitative tightening (QT).

Inflation in Canada is higher and more persistent than the Bank expected in its April Monetary Policy Report (MPR), and will likely remain around 8% in the next few months. While global factors such as the war in Ukraine and ongoing supply disruptions have been the biggest drivers, domestic price pressures from excess demand are becoming more prominent. More than half of the components that make up the CPI are now rising by more than 5%. With this broadening of price pressures, the Bank’s core measures of inflation have moved up to between 3.9% and 5.4%. Also, surveys indicate more consumers and businesses are expecting inflation to be higher for longer, raising the risk that elevated inflation becomes entrenched in price- and wage-setting. If that occurs, the economic cost of restoring price stability will be higher.

Global inflation is higher, reflecting the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, ongoing supply constraints, and strong demand. Many central banks are tightening monetary policy to combat inflation, and the resulting tighter financial conditions are moderating economic growth. In the United States, high inflation and rising interest rates are contributing to a slowdown in domestic demand. China’s economy is being held back by waves of restrictive measures to contain COVID-19 outbreaks. Oil prices remain high and volatile. The Bank now expects global economic growth to slow to about 3½% this year and 2% in 2023 before strengthening to 3% in 2024.

Further excess demand has built up in the Canadian economy. Labour markets are tight with a record low unemployment rate, widespread labour shortages, and increasing wage pressures. With strong demand, businesses are passing on higher input and labour costs by raising prices. Consumption is robust, led by a rebound in spending on hard-to-distance services. Business investment is solid and exports are being boosted by elevated commodity prices. The Bank estimates that GDP grew by about 4% in the second quarter. Growth is expected to slow to about 2% in the third quarter as consumption growth moderates and housing market activity pulls back following unsustainable strength during the pandemic.

The Bank expects Canada’s economy to grow by 3½% in 2022, 1¾% in 2023, and 2½% in 2024. Economic activity will slow as global growth moderates and tighter monetary policy works its way through the economy. This, combined with the resolution of supply disruptions, will bring demand and supply back into balance and alleviate inflationary pressures. Global energy prices are also projected to decline. The July outlook has inflation starting to come back down later this year, easing to about 3% by the end of next year and returning to the 2% target by the end of 2024.

With the economy clearly in excess demand, inflation high and broadening, and more businesses and consumers expecting high inflation to persist for longer, the Governing Council decided to front-load the path to higher interest rates by raising the policy rate by 100 basis points today. The Governing Council continues to judge that interest rates will need to rise further, and the pace of increases will be guided by the Bank’s ongoing assessment of the economy and inflation. Quantitative tightening continues and is complementing increases in the policy interest rate. The Governing Council is resolute in its commitment to price stability and will continue to take action as required to achieve the 2% inflation target.

For context:

The interest rate pre-pandemic was 1.75%.

The interest rate today is 2.50%.

So all that talk about “getting to pre-pandemic interest rates” is not only spot-on, but it’s actually in the rear-view window because we’ve now flown past that.

Now, pop quiz: when was the last time the benchmark rate was at 2.5% or higher?

Can anybody tell me, without looking?

2008.

It’s been fourteen years since we’ve seen this type of interest rate environment, although it’s not for lack of effort on the Bank of Canada’s part.

The rate hit a low of 0.5% on July 15th, 2015 and remained there until July 12th, 2017, when the rate increased to 0.75%.

Two years at 0.5%.

The rate increased again to 1.00% in September of 2017.

The rate then increased to 1.25% in January of 2018.

In June of 2018, the rate increased to 1.50%, then to 1.75% in October.

And there, the rate sat, until a little something called “The COVID-19 pandemic” happened. In March of 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, the Bank of Canada dropped the rate from 1.75% to 1.25%, then a mere ten days later, dropped the rate to 1.25%. “Extrordinary times,” we were calling them, after all. Another 50 basis-point cut happened two weeks later, and within March alone, we saw rates go from 1.75% to 0.25%.

That is how we got to this point.

And that was never supposed to happen.

COVID made it happen, and if not for COVID, these interest rates would have arrived much sooner.

The benchmark lending rate sat at 0.25% from March 27th, 2020 through March 3rd, 2020; almost two full years!

As I said, this was never supposed to happen. Quantitative tightening was well underway in 2017 and 2018, and while we remained at 1.75% for 17 months, from October of 2018 through March of 2020, I do believe the point was to keep rates from falling, if not for COVID.

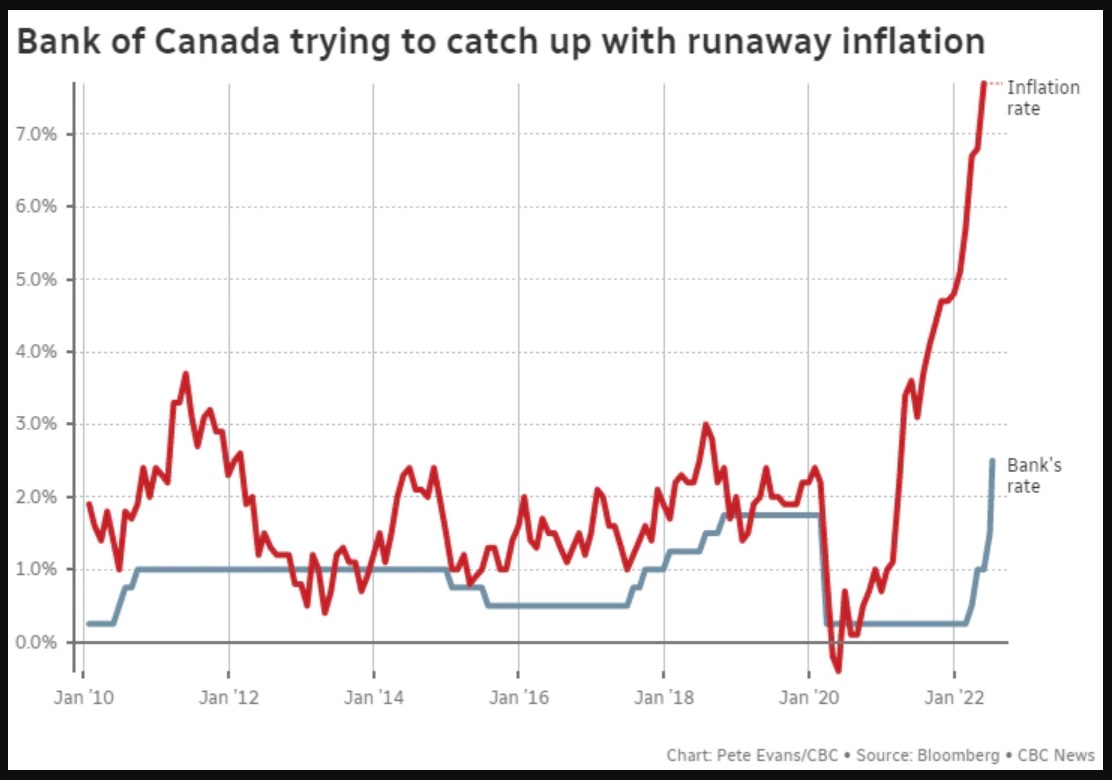

There were no shortage of articles on the interest rate hike last week, and no shortage of great graphics.

Here’s one from the CBC article, “Bank of Canada Hikes Rate To 2.5% – Here’s What It Means For You.”

I don’t know that there’s a more important chart out there right now.

Trust me. I spent a long time searching for this over the weekend!

For reference, consider that any central bank sets the ‘ideal’ rate of inflation around 2.0%, so over the last decade, the country did very well overall.

But you don’t need to be a statistician or an expert in technical analysis to look at the above chart and conclude, “Something looks off.”

That chart is why some people believe further rate hikes are on the horizon.

If you don’t subscribe to the Finacial Post, they were the media outlet who got an exclusive with the Bank of Canada governor, Tiff Macklem last week,

Here’s the article:

This is behind a paywall, so here are a few choice questions and answers:

Kevin Carmichael: Is it fair to say that the primary mission today was shock and awe, to reset expectations around inflation?

Tiff Macklem: I’ll let you pick your favourite expression. I think it is fair to say that today’s decision expressed concern. I didn’t like your word, “panic.” (The decision) expressed concern that inflation is too high; it’s affecting all Canadians. And it expressed concern that the longer inflation stays too high, the bigger the risk that this high inflation becomes entrenched in people’s expectations.

Kevin Carmichael: What’s the best way to think about how inflation expectations work? That is, won’t people need to see inflation start to come down? Or are you convinced that a surprisingly aggressive move is enough to rest those expectations?

Tiff Macklem: Ultimately, Canadians will definitely need to see inflation coming down. They’re going to believe that inflation is coming down when they see it’s coming down.

But Canadians understand what’s going on. They understand that there are shortages in the economy. We’re all seeing shortages of workers. We’re all seeing shortages of goods and services. You buy something and it takes longer (to arrive). You want to go to a restaurant, it’s harder to get a reservation. You want to fly somewhere and the airports are clogged. We’re all seeing evidence. Canadians understand that the economy is overheated and it needs to cool. We’ve got to slow down spending, give supply the opportunity to catch up to take some steam out of inflation. If Canadians thought that we (at the Bank of Canada) didn’t see, and we didn’t understand that, that would be unnerving; that would start to unmoor inflation expectations.

Kevin Carmichael: Could you address the critique that you, the Fed, the big central banks are now overdoing it when it comes to inflation? That you’re now pushing forward too aggressively and the economy is going to suffer more than it needs to as a result?

Tiff Macklem: Front-loaded tightening cycles, typically, lead to softer landings. The other way to put that is, more gradual tightening cycles that end up having to take rates even higher end in bigger slowdowns. So, we are deliberately front-loading our policy response. Our objective is to get inflation back to target with a soft landing, and a front-loaded policy response gives us the best chance of achieving that.

Are we over doing it? We raised rates by a very big step, 100 basis points, but the level is 2.5 per cent. It’s not a high interest rate. You have to look at where we started. We started effectively at zero. Yes, we’ve raised rates quickly since March, in four steps, and it’s an unusually rapid increase, and that reflects the fact that the economy has moved rapidly into excess demand, and what started as international inflation coming largely from higher oil and higher prices for globally traded goods because of gummed up supply chains, what we’re seeing is that is broadening in Canada, and with that broadening, it’s persisting.

Kevin Carmichael: Monetarists are arguing forcefully that if central banks had kept a closer eye on money supply that we wouldn’t be in this mess. To what extent does Governing Council consider money supply when it’s making its decisions? And what’s your response to the broader notion that money aggregates had something to tell us all along?

Tiff Macklem: We do look at everything. We look at money growth. We look at credit growth. The thing about money growth, though, is that it’s a good predictor, some of the times, and then it’s not such a good predictor at other times. Money growth, it can be an indicator of spending, people need money to spend, but the inflationary impact of that spending, depends a lot on the state of the economy. If the economy is weak, and it needs extra spending because it’s like filling in a hole, that’s not inflationary. That’s filling in a hole. That’s preventing inflation from going down.

On the other hand, if your economy moves into excess demand, yes too much spending causes demand to run ahead of supply, supply can’t keep up, and inflation goes up. So, yeah, sometimes money is a good predictor of future inflation, but sometimes it’s not. Yes, you can draw a graph and you can see that money growth went up a lot in Canada, in the depth of depths of the pandemic and now inflation is high. On the other hand, if you go back, the Bank of England, for example, after 08-09 had very large quantitative easing programs, big surges in money growth and we did not see big surges in inflation after the global financial crisis.

I would have loved to see Kevin Carmichael ask about the excess spending by all levels of government (specifically as it pertains to gaining votes and getting elected; something I’ve lamented over the years), and how all the extra money in the economy has contributed to inflation, but perhaps he did ask this in the last question.

So, with all of this out of the way, let me introduce Wednesday’s blog post.

This week, I am going to interview my mortgage broker, Tony Della Sciucca. Tony is not just a source for interest rate predictions and entry-level queries like, “should I go variable or fixed?” Like myself, Tony has a background in economics and studies fiscal and monetary policy just for fun.

On Tuesday afternoon, I’ll interview Tony over Zoom and ask him your questions.

I’ll start a thread below for questions.

I’m sure the rest of you want to discuss, debate, and opine, so the rest of the comments section will remain open.

[ad_2]

Source link

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-559025517-2000-b3bece30a9074ec3958a4d39f69f2a79.jpg)